Vignettes for my Father

Family stories not only piece together a person's life story; they also revealed bits of historical context.

My father was born 115 years ago February 1st. Here are a few vignettes in honor of his storytelling and how those stories enriched my love for him as well as taught me how worldwide historical conditions affected daily life.

Dinner With Dad

While Mom lay sick with cancer in her bedroom, Dad and I sat at the kitchen table, wedged into a space so tight his chair backed into the hall. Usually, I would heat up a can of Campbell's soup or throw together a casserole and we'd eat.

Pressing his finger against his cheek during a pause in conversation, the indentation remained in his aging skin. He'd tell stories I still crave about how he and Mom met, how she surprised him with a chess set he wanted to buy. How they both wished they had stayed in Phoenix after the war instead of coming back home to families. That's when they started arguing every night as my sister and I lay in bed.

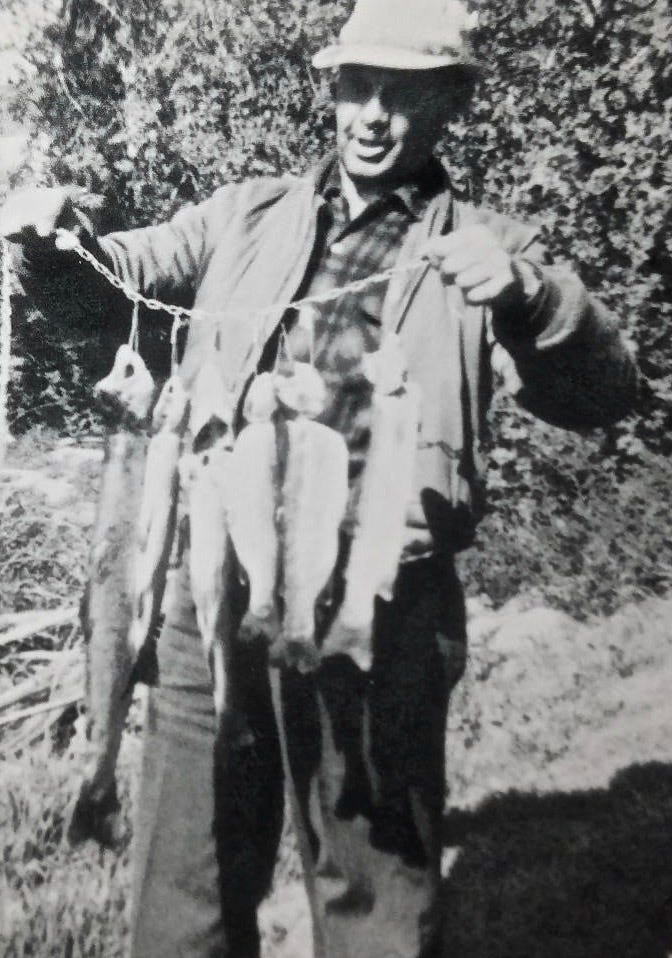

Before he and his buddies got married, they went fishing every weekend. In the Depression, there were no limits on how many fish they could bring home. They'd leave Saturday night after work and return Monday morning, the lucky ones because they all had jobs. In fact, his boss hired him right out of class a month before he graduated from high school. He never tired of being an electrician all his life.

He told me about the Model A Ford he was able to buy. "Those cars were only $400, but nobody had $400," he said. He had a camera then, too. That's how he met Mom … at the camera counter in ZCMI. I still have the photos his friends took of him, that old Model A, and the long string of trout he caught to take home.

There were so many stories about his youth that hinted of those Depression times. What he didn't tell me, though, was how those fishing trips not only brought food to the table, but he would often leave just before dinner so there would be more food for his mother and five siblings.

Wall-to-Wall Sunshine

His voice grows raspier each year but I can still hear his smile over the phone. First thing he says before anything else is how the weather is. More than likely it's wall-to-wall sunshine. Maybe he'll convince me to come back home where the weather is almost always perfect.

Despite what people tell me, who see him every day, he's doing fine. Just ask him. Living alone in the same house that sheltered my childhood, he has his dog and cat that follow him on daily walks. Also there's his routine recited every time I call: breakfast at the bowling alley here he use to play in a league then to the bank where they greet him by his first name. Some days he visits his brother to complain about whoever lives in the White House.

He holds court with me at least once a month. I know he would like to hear more often about our lives far away, but as soon as I start to tell him our latest news, he launches into another story. Maybe one about him and Mom or how he saw his friend, Little Jimmie, who's been dead for a year, crossing the street right in front of his car downtown. And we talk about that for a while.

Soon it's been over an hour.

"You're buyin' the farm, girl," he would say with a chuckle.

"No Dad, it's nothing. This is my only chance to be with you," and a little bit of home.

I think about him sitting by the phone that one day when he figures I'll call, waiting. If I miss that day … will he be …? I really don't want to think about it. Because after we say goodbye and I love you Dad, there's always that little pause just before the click. Each time I wonder will it be the last time we talk about wall-to-wall sunshine?

A Drawer of Tiny Books

Shoved in the back of the closet of my childhood bedroom, Dad's Daily Diaries collected in an old metal desk drawer. I wondered where it came from; his army desk or some castaway he found during a trip to the dump? Wherever, the divided drawer held dozens of tiny books, lined up in proud succession like soldiers, each carrying a piece of his life. Each page revealed those things he considers important:

when the cat ran away and returned pregnant a week later

how many tomatoes he harvested this year. "Did Mrs. Troxler steal any?"

dates for oil changes, tune-ups, tires purchased or rotated

the year his bowling team won the tournament

the date Mom died, the date buried.

I wanted to read them all and learn more about my father in his own simple script.

He even recorded weather conditions, changes in the climate and the health of his gardens. I thought that was significant information to plot into a chart program. He told me he suspected the military projects in Nevada and Dugway were polluting the air and soil. I don't know if he ever knew we were Downwinders.

Of all the stuff he left behind in that old house on Redondo, I wanted those tiny books. I was too late, however, for the toss-out party my sister held after he was laid

to rest next to Mom. I didn't make it in time to help her with Mom's things decades earlier when she died. Instead I stood, speechless, as Becky sent 1940s hats and purses spinning across the floor, mocking each item with wicked laughter.

"Aren't they hilarious? Can you believe Mom wore these hats?"

She said I could have the garish painting over the hearth, though, the coffee table I scratched doing homework, and the rocker nobody wanted. I remembered Mom holding me there, humming lullabies in my ear.

"Sure, I'll take the table and rocker, but what happened to his little books?"

What books was I yammering about?

"Oh those -- they were junk, like everything else here. It's all junk. We threw them in the trash last week. You'd think he had made more money after all these years. There was only the thirty grand he hid in that cash box and that wallet he placed on top of the box. You can take that wallet home with you. We put the money in the trust account. We didn't find any more, though."

"Well, he sent us hundred dollar bills for birthdays and Christmas, even Mother's Day. Remember those beautiful frilly cards he sent us? We've been getting our inheritance for years."

I didn't even try to explain how much I cherished those tiny books in that drawer.

All photos furnished by Sue Cauhape.

oh the loss of those little books is heartbreaking. having lost my dad to a heart attack when he was 43 and I was 15, stories about aging fathers written by adult daughters always tug at my heart. lovely piece, Sue.

I’m heartsick on your behalf over the loss of those little books. I’m leaving many notebooks that my children are free to throw away. Most of my work is on my hard drive, though, and nobody will bother to look at it there.

Where do you keep your notes and impressions?