Truth Be Told

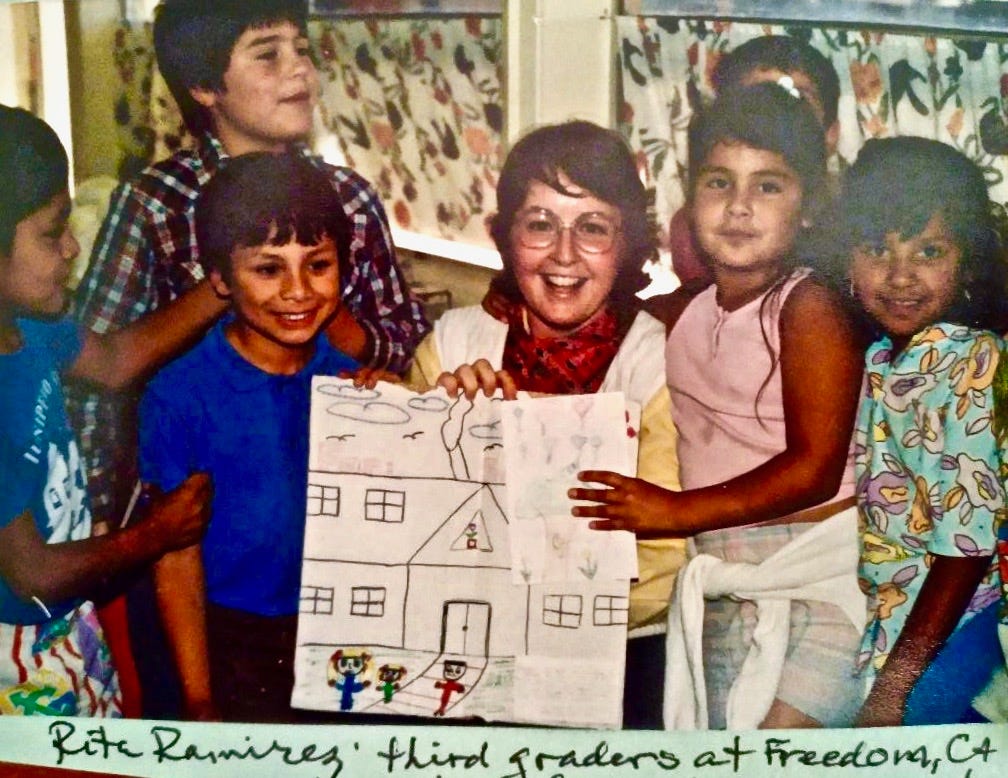

No sooner had I sat in the chair than Marisol and Hector draped their arms over my knees, awaiting the stories. Their teacher, Rita Ramirez, told me they responded better to storytelling than any other learning activity.

She commissioned my weekly sessions through an artists' network to help her students learn English. Every Friday, they gathered around as I shared tales from many different cultures. Of course, they all related well to Mexican stories, especially La Llorona. It's a legend about a woman, spurned by her lover, who drowns her children in the river, only to spend Eternity bewailing her loss. Obviously, this story portrays a range of adult subject matter, but the children related to it personally. One little boy said he had actually seen this ghostly figure walking along a river near his home.

Mexicans are not timid about teaching their children the hardships of life within the safe context of stories. What's more, they don't separate the audience into "children" and "adults." The whole community is gathered to hear the narrador. And their ghost stories … ay, dios mio … can be horrific. Nevertheless, this is a time-honored method of transmitting histories and social mores.

I made it a goal for any of my programs to include five different cultural expressions around a specific theme: family, how the earth came to be, relationships between people, heroes and heroines, how animals became how they are, how to solve problems, and how to deal with troubling feelings.

It's interesting to see how various races and classes of people react to storytelling. For middle-class whites, storytelling is a way to calm rambunctious children. After a certain age, other activities are more acceptable. I've actually had to tell parents to stop talking in the back of the room while I struggled to be heard by their children only a few feet away.

Also, there's that kid who asks that eternal question posed to every storyteller, "Is that story really true?" I always say, "there's a kernel of truth in every story," and that seems to put the question to rest for a while. One brilliant storyteller answered a curious child with, "I've told lots of true stories that never happened." In fact, Mark Twain made a career of writing news stories for the Territorial Enterprise by making stuff up if nothing exciting happened. He soon became America's most famous and esteemed raconteur.

Fact usually doesn't have a central place in the fictional world. Instead, it hides within the folds of metaphor and imagery. Plotlines must be plausible and not defy the rules of physics, but the teller can stretch the plot and characters any which way as long as she doesn't obscure that tiny kernel of truth.

Thus, a simple adventure told around a campfire or over a beer promises to morph into a glorious lie. Whoever retells that story begins the grand process known as "the folk tradition." Even taking a folktale from a book is allowed some latitude in customizing it for the time or the audience.

One dramatic example this is when I arrived at a local summer camp. I walked into a room where a dozen or so adolescent Black boys fidgeted and elbowed each other. After performing several gigs in front of jaded middle class kids, I swallowed hard and marched forward, determined not to show my fear of their energy.

To start, I told them "Bloody Fingers," from Alvin Schwartz's Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark. While I acknowledge him as the source, I did have my way with it. Schwartz's collected folktales after all, so unless I memorized his version, there was no copyright infringement.

Unlike the book's version, mine included a liberated woman traveling to a business meeting. She ran away just as fast as the salesman who stayed in the room before her. A hippie eventually put the ghost in its proper place. It was a well-practiced version that delighted teachers as well as their students. I hoped it would work with these boys.

As soon as I delivered the punch line, the room exploded!

"Oh, I've heard that story before," one boy jumped up and yelled. "Can I tell my version? I love that story." I nodded for him to take the floor and a robust Round Robin ensued. It was amazing how many versions they all shared that afternoon

And where did they first hear it? Schwartz's book or from their siblings? Was it handed down through generations? Did they hear it on the playground among friends? It was obvious, though, they didn't think they were too cool to listen to some old white lady tell kid's ghost stories. What's more, we had a wonderful time putting "Bloody Fingers" through the folk process.

My illustrious storytelling career spanned seven years in the late 80s. I joined the Santa Cruz Storytellers, an eclectic group of performers who organized concerts for everyone from toddlers to seniors in all kinds of venues. One place was a lunchtime story hour in a downtown courtyard. At first it hardly drew a soul, but word got out. By the end of summer, it was standing room only for shoppers and office workers who munched on their sandwiches as we told folktales, legends, and myths. All of them were adults, mostly white. They were discovering the magic.

A mime once advised me, "When you're working the street, never say no." So, I figured no story was off limits. For me, it was a fun way to broaden people's worldview. While I hoped the multicultural programs would enhance teachers' lesson plans, I was surprised how the power of story deeply affected adults.

During a Japanese festival, I was stationed in a little hut within a beautiful garden. Student groups would come and go in shifts. One group of teens was led by two men. As the students found their seats in the tiny space, one of the men said, "So where's the screen? Are you doing Disney?"

I brought out the heavy artillery, The Old Man Who Made the Trees Blossom, a story of a man whose efforts to get along with his belligerent neighbor brought forth a miracle of dead trees blossoming. Both teachers were moved to tears.

By not limiting ourselves to specific genres and cultures, our storytelling group was able to present a variety of pieces to our audiences. Storytelling was popular during the 80s, with some credit going to the PBS special where George Lucas interviewed his mentor, Joseph Campbell. This seemed to give adults permission to enjoy an evening of tales told by practitioners of what is called "theater of the face."

Further proof of that is the long-running Sierra Storytelling Festival help every June in Nevada County, CA (

https://www.sierrastorytellingfestival.org/

). Called the "queen of storytelling festivals," it draws performers from all over the world to entertain and enrich mature audiences.

Imagine it. A lone performer stands on an empty stage. The lights narrow to a spotlight on the teller. Soon their voice resonates across the room. As the rustling quiets, the voice fills the space. In the end of the performance, there is a deep silence for a moment as the audience breathes in the magic.

Of course, this image depends on the size of the room and the audience. Among the many performances during the Clinton inaugural events, Diane Ferlatte walked on to a huge, brightly-lit stage at the Children's Concert. Dressed in a costume with stiff, square-legged pants and puffy sleeves, she looked much larger than she is. While telling the African folktale, The Big Wind, she moved around that vacant, unadorned stage, blending dance with wide arm movements. Her magnificent voice boomed across the audience, entrancing the children with every word. Truly a stunning performance, and so different from how she barely moved when I saw her perform in a meeting room of a library.

My gigs included schoolrooms, town meeting halls and libraries, stages in parks and festivals, and the living room at the home of Ed Sundberg, who mentored some of us after his class at the community college. My favorite places, however, were with my Mexican elementary and high school ESL students.

There were two sessions a year at Watsonville High School: one focusing on folktales and the other telling a version of Shakespeare's "Romeo and Juliet." I was warned these students' English skills were rudimentary at best, therefore I had to keep it simple. That was challenge enough, but somehow I needed to squeeze "Romeo and Juliet" into a 40-minute time frame.

It went well and I really enjoyed the energy at the school. There was a gigantic mural of beautiful Mexican folk images painted on the side of a building I passed every time. Sometimes, though, I wondered if this exercise in spanning language barriers was working.

During one class, I watched a boy sitting in the back row contemplating his naval, a blue bandana tied around his head. Not once did he allow eye contact. Well, we've lost him, I thought. The teacher later informed me that he had come to her after class and said, "That was a real good story." Bingo! There's always a surprise.

During the folktale sessions, I usually started with "How the Men and Women Got Together," a sexy little number to draw them into a rapport with this old white lady. You can always connect with teenagers when you talk about sex. Once they knew what I was capable of, telling them Shakespeare a few months later was so much easier. We had connected and they looked forward to it.

These experiences with Hispanic listeners also showed how they were far more receptive to storytelling than white teens, who were "just too cool" for kid stuff. Those of us in the Storytellers discussed this phenomenon. Had television and their parents' detached attitudes dulled their imaginations and attention spans? Had the rich Mexican culture created a mindset where storytelling was a community event for all ages? The immigrant kids always seemed a lot more engaged. Maybe it was because they were more in touch with old traditions despite their exposure to American media.

One story in particular, along with a freakish bit of luck, revealed the pre-Christian beliefs that some of those students still held.

It was a tempestuous day, rainy and blasting with a ferocious thunderstorm. I started telling an Iroquois legend about a young hunter who sought refuge from the snow under a massive boulder overhang. The stone rumbled and woke him from sleep. "Now I will tell you a story," it announced with a booming voice. And the stone instructed the youth about how the animals came to be and why certain things happen in the world. The hunter then took these stories home to entertain his people during winter in the longhouse.

This particular day, timing was phenomenal. Each time I said, "And the boulder rumbled," thunder would accompany that phrase. The first time it happened, the students laughed. "Wow, that was cool!" The second time, I was so amazed it happened again, I laughed. Would it happen again? The anticipation heightened.

The third time, I held my breath. We all held our breaths, awaiting the voice of thunder. It roared after the briefest hesitation. A girl in the back row stared wide-eyed at me as she gasped, "Bruja!"

It was such a crazy experience, I wondered if she wasn't correct. Nah, don't be so arrogant, I whispered to myself. You don't have that kind of power.

It was true, though, that the stories have the power, as a means of teaching, of gaining trust, and of awakening that capacity to visualize how humans live, solve their problems, and share their dreams. Much like music, the human voice telling a story goes right into the sternum and vibrates against the heart.

People are never too old to hear a good story whether it's around the campfire, in a living room, or in a concert hall. Humans love and need stories. Why else would our ears perk up to the strains of the latest gossip?

Post Script: recently I've discovered a wonderful storyteller, Jake Evans, you can find on https://www.facebook.com/jakeevansstoryteller. It's gratifying to know that social media has become a viable platform for storytellers to continue to enrapture people around the world.